This is the transcript of my presentation at the Southernmost Open Forum on Nov 11.

The slides I used can be viewed here.

Photo credits: Lim Sim Lin for Emergency Stairs

Embedding / Dwelling: being intimate with Southernmost

Hello everyone, it’s good to see all of you here. Thank you for coming.

For the past week, I’ve been “critic-in-residence” at the Southernmost festival. I use air quotes to describe my role because I realise I have been many things. I have been a witness, an ethnographer, an archivist, a participant, an observer, a writer, a performer, a student, a critic, a listener, a supporter, a researcher, a provocateur, a voiceover, a dramaturg – and a friend. I’ve titled this presentation “embedding” because of what it has been like to embed oneself in the front lines, down in the trenches; but also “dwelling” because I have learnt what it is to be with and commune with everyone who was a part of Southernmost, to make this place my temporary home.

If you’re wondering why I’m the only Open Forum speaker without a partner, my dialogue partner is actually supposed to be Southernmost itself. So I thought I would give you a very brief overview of what happened throughout the festival before asking some questions of my non-speaking dialogue partner.

Over the past week, from 9am to 6pm each day, the seven featured artists of the festival, whom you can read more about in your programme booklets, have come together for an enormous undertaking. They’ve embarked on a performance research project, the main thrust of the festival, where they’ve had dramatic encounters and intense conversations with each other. All of them come from performance lineages that we might describe as the “traditional”, but which I’ve come to realise is a reductive and monolithic term for performance forms that are ever-evolving, whose practitioners are experimental, irreverent, slippery, sinuous and extraordinarily powerful.

We began the week with workshops, where each practitioner got to spend one hour with every other practitioner for a one-on-one, bespoke masterclass. It was up to the “teachers” to decide what to teach their students, but it was up to the “students” to direct the eventual five- to ten-minute presentation that resulted from the process of teaching and learning. We would then all have a group discussion about what we had experienced.

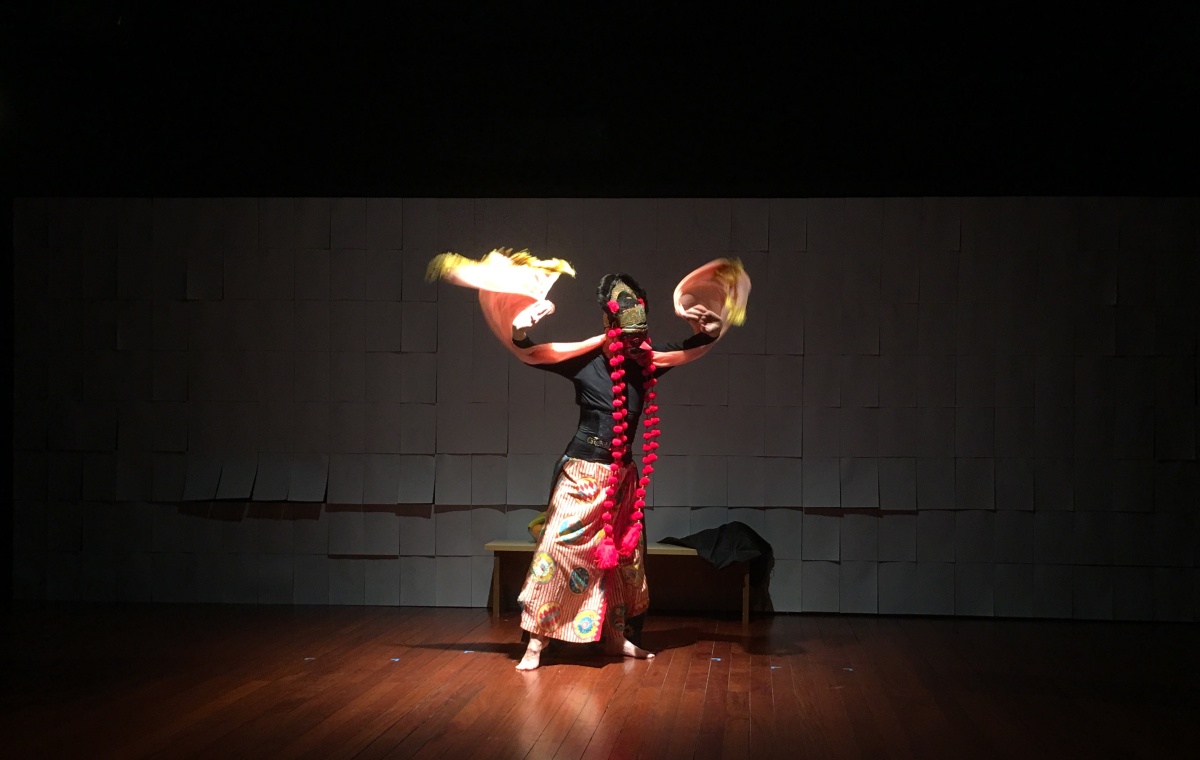

Through this process we interrogated modes of knowledge production and transmission, of what happens when bodies learn the vocabularies of other bodies, of new pedagogical approaches for the various performance forms, of negotiating boundaries with the state, of the different and similar challenges each cultural, national and political context poses. All this is the work that has taken place underneath what you have seen, or will see of Journey to Nowhere. In that sense, Southernmost has acted more like a performance incubator or an intensive academic programme, with workshops, masterclasses, small-group discussions, showcases, and a symposium-style forum like today’s – dedicated to the artists who have been invited to participate in this festival. The fulcrum of the festival is not the Journey to Nowhere production, although it does allow you a glimpse of the playfulness and transgressiveness that the artists have relished over the past week, dismantling boundaries between what we assume to be the “traditional” and the “contemporary”. While Journey to Nowhere has a very strict structure, every scene was based on a devising process by the featured practitioners, who collaborated with Xiaoyi to produce what you’ll have seen or will see later today. There’s also the thrill of improvisation and arbitrariness built into the production, even if the audience might be less privy to the mechanics of the performance that takes place beyond this stage.

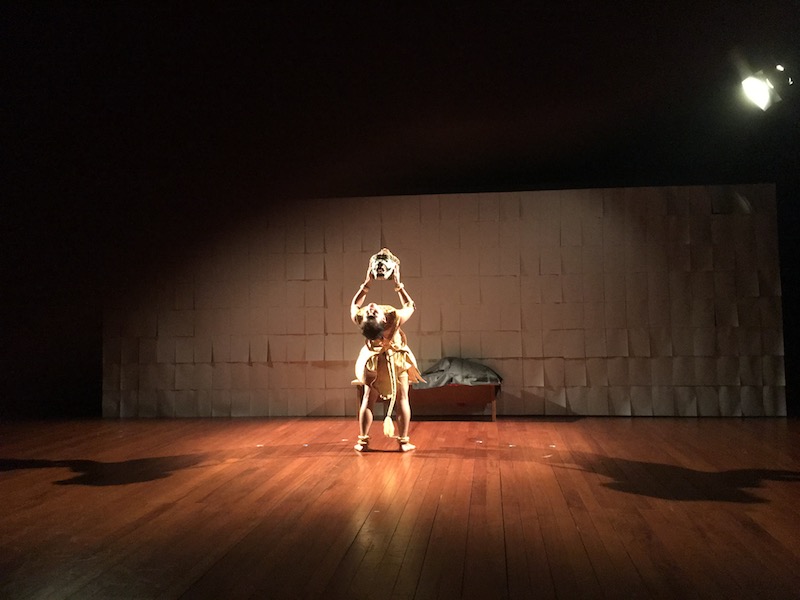

What I’m really sad to have missed were the nightly masterclass workshops conducted by Didik and Rady. But I did get to see the presentation by their students, who knit together what they were taught with their own attempts at experimentation. And what a privilege to be able to witness Shimizu-san, Didik and Rady perform what they have spent decades of their life dedicated to honing and perfecting – I think those were two evenings that we will cling to and savour, to feel that electric shiver of connecting to something much larger than we can comprehend, and then being able to engage with these incredible performers about their work after.

I won’t go into further detail because you will be able to read most of this on my website, but I thought I would go into some of the questions I have for Southernmost. And these are questions that I hope will linger. They aren’t meant to be defended, or answered now, or even within the next few weeks or months, or maybe even years. All I ask is that you might sit with these questions for a while.

(1) How can we shift audience’s expectations of the Journey to Nowhere performance – so that they see it not as a “culmination” or a “final product” but as a platform for experimentation, joyful irreverence and play?

I think most of the immediate feedback I’ve heard from audiences who’ve come to see the showcase is that they aren’t quite clear how it connects back to the workshops or ethos of the festival. The showcase wrestles with a lot of notions about what we expect intercultural engagement to look like, and I’ve heard audiences wonder why it looks like a “work in progress”, or why the masters didn’t do a “traditional” traditional performance in Journey to Nowhere. In some parts of the production, we see the performers referencing performance forms that are not their own in very subtle ways, like Rady fusing the sharp, precise head tilts from his masked dance with the silat movements that Amin taught him, or Didik borrowing from the delicate heel-toe movement of Chinese dance, inspired by Elizabeth – but so much of this is inaccessible to those without, as Bourdieu would put it, the key to decode the gestures and movements they are seeing. They could interpret these movements independent of the weighted histories and granular detail attached to them, but I think that would be such a shame, to lose that layer of knowledge. I also wished that we could better communicate how the practitioners are here to cross borders, to leave the confines of what they are expected to perform or how they are expected to behave as “traditional artists”, and to revel in what they cannot do on other platforms, with mischief and glee.

Which leads me to:

(2) How can we make this artistic process more visible? How can we encourage audience members to become ‘spectator-collaborators’?

I think the work that Southernmost is doing is vital and profound. But I understand how it can be difficult for audience members to excavate, to go beneath – especially if they don’t have time to attend the open rehearsals or the masterclasses. It took me an entire year, as well as this process of “resident” and “embedded” criticism, to understand what Emergency Stairs is trying to scratch at, to learn the language they use, their specific performance vocabulary, and the questions they are asking of our art and of Asia. Is there a way we might invite audience members to invest interest in this project throughout the year? Is there a way we might encourage them to pleasure in making meaning of the stage, that the images we give to them are open-ended and available for multiple interpretations?

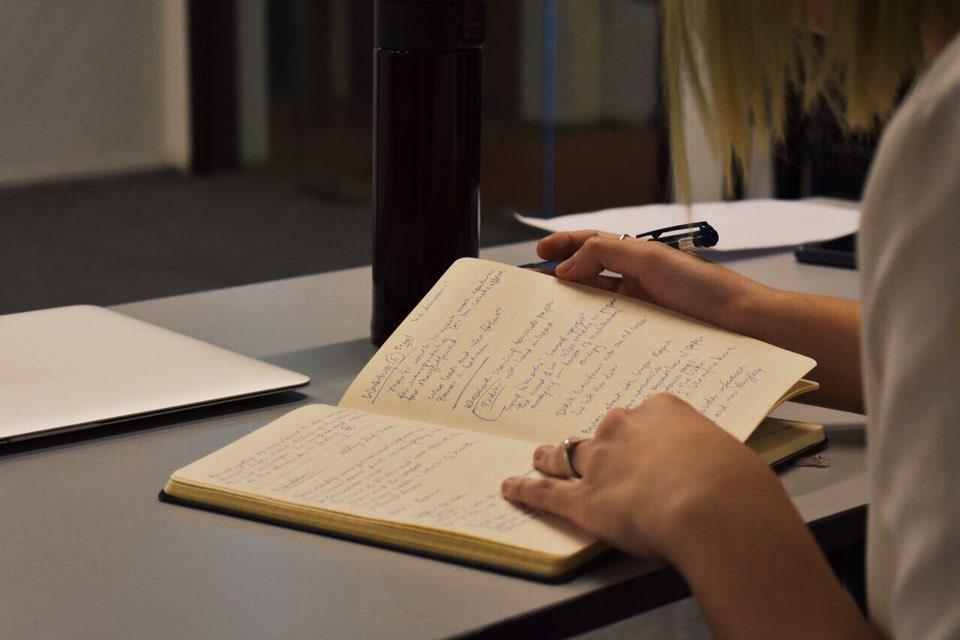

To give you a sense of the labour behind the performance, and the fun had, this is the script of the production, which is basically a performance score that can also contain improvisations. And this is what four of the performers were doing to decide in which order they would enter the space for one of the scenes.

And finally:

(3) Should we be using the work and bodies of international artists to comment on Singapore-specific cultural policies, even if these policies are markedly similar in their own countries? Is this their burden to bear?

The National Arts Council’s SG Arts Plan (2018-2022) forms the framework of Journey to Nowhere, and during our rehearsal process Xiaoyi talked about how the performance was one of his responses to and negotiations with what he saw as a five-year, durational script provided to him by the state. Each of the artists shared the challenges and triumphs they’d faced and accomplished in their various cultural and national contexts, both Singaporean and non-Singaporean. But the framework for Journey to Nowhere is very much a specific Singaporean one, with particularities to this local context that may not be the struggle of other artists. I must say that Didik, Rady and Shimizu seemed more than delighted to collaborate with us to make sense of Singapore’s cultural policy, but I wonder if this is their burden to bear.

Because Southernmost cannot respond to me, I didn’t think it fair to end this presentation on such an interrogative note.

So I wanted to end with gratitude instead, with a series of thank-yous for Southernmost.

(1) Thank you for inviting me in.

It’s hard to think of many performance companies in Singapore who would willingly open their doors to a theatre critic, and to have basically allowed me to do whatever I wanted with this platform as “resident critic” – or “resident writing participant”, as Elizabeth put it. This has been a transformative process for me, and I have learnt so much from simply being in the same space as all of you. I have tried my best to sit with you and write with and about you this week, but also for you, and everything I have written is my gift to you. You can use it in any way you like. In the same way you have gifted performances to audience members, allowing them to think and respond in any way they wish to it, this gift is no longer mine – it belongs to you.

(2) Thank you for giving practitioners a community, and room to play – and for all the kindness and generosity you have shown us as guests in your home.

I’ve been having conversations with all the artists involved this week, and a recurring refrain is how cared for each of them feels. Some have told me about how amazed they are to have had an equal voice with everyone else, such that no one felt neglected at any time. You worked around the demanding schedules of all the artists: we didn’t have Andy around for four days because he was performing in Australia; Shimizu-san flew off on Wednesday night to Tokyo to perform and returned yesterday morning, just hours before the first matinee; Ee Vian had to leave for several hours at a time to teach her private students. In the same way, the artists moved mountains to be here, altogether, even if the cast was at full strength for only two hours. And everyone told me that they felt heard, that they were listened to, and that they were finally understood.

(3) Thank you for being brave.

This has been such a difficult undertaking. I’ve seen you struggle to convince the public of the value of these performance forms. I’ve seen the box office receipts and the financial risk you’ve taken on to get this festival off the ground. I’ve seen the criticism and frustration you’ve had to engage with – some of it my own, from my previous reviews of your work – with patience and grace. I would like to acknowledge and thank you for that.

That’s all from me.

Thank you.